Blog

How Many Molecules Are in That Glass? Mastering the Art of the “Estimation Question” for Future Oxbridge Scientists

It’s a classic Oxbridge interview question: “How many molecules are in that glass of water?” To a student used to rote memorisation, it feels like a trick. To a future scientist, it’s an invitation to think.

These kinds of questions have a special name in scientific circles: Fermi problems, named after the legendary physicist Enrico Fermi, who was famous for making remarkably accurate estimates using nothing but logic and basic principles. And while they might seem intimidating at first glance, they’re actually one of the most rewarding types of problems a young scientist can learn to tackle.

At Success in STEM, we believe that helping students master these estimation questions does far more than prepare them for tricky interview scenarios. It builds the kind of deep, flexible scientific thinking that serves them well in exams, at university, and throughout their careers.

The Fear of the Blank Page

There’s a particular kind of panic that sets in when a student faces a question they’ve never seen before. No formula to recall. No worked example to mimic. Just an apparently impossible question and the expectation of an answer.

This is what we call the “blank page” moment, and it’s where many students freeze.

The truth is, estimation questions aren’t designed to catch students out. They’re designed to reveal how a student thinks. The interviewer or examiner isn’t expecting a precise answer pulled from memory. They want to see the logical steps you take to get somewhere reasonable.

When a student understands this, something shifts. The question stops being a threat and starts being a puzzle. And puzzles, as most young people intuitively know, can actually be quite enjoyable to solve.

We see this transformation regularly in our sessions. A student who initially says “I have no idea” gradually realises that they do, in fact, have plenty of ideas. They just need to learn how to connect them.

Breaking It Down: The Three-Step Framework

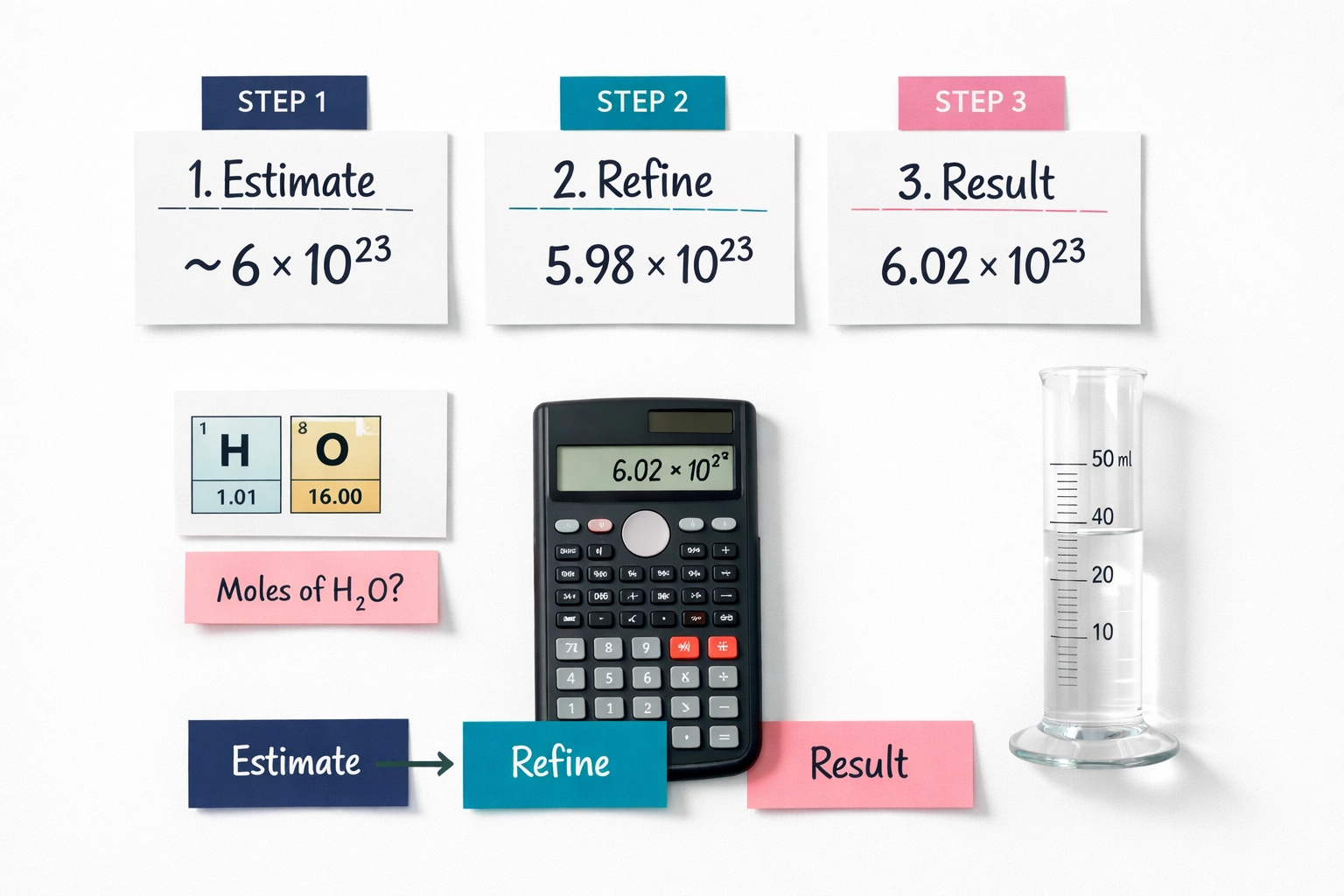

So, how many molecules are actually in a glass of water? Let’s work through it together, using the same approach we teach our students.

The key insight is that you don’t need to know the answer. You need to know how to build towards an answer using information you already have.

Step 1: Start With What You Can Measure

A typical drinking glass holds roughly 250 millilitres of water. Since water has a density of approximately 1 gram per millilitre (a useful fact that crops up repeatedly in GCSE and A Level science), that means our glass contains about 250 grams of water.

Already, we’ve made progress. We’ve converted a vague “glass of water” into a concrete number we can work with.

Step 2: Convert Mass to Moles

Here’s where basic chemistry knowledge becomes powerful. Water has a molar mass of 18 grams per mole (since H₂O contains two hydrogen atoms at roughly 1 g/mol each, plus one oxygen at 16 g/mol).

If we divide our 250 grams by 18 g/mol, we get approximately 13.9 moles of water.

Step 3: Convert Moles to Molecules

This is where Avogadro’s number comes in: 6.02 × 10²³. This tells us how many individual molecules are in one mole of any substance.

So, 13.9 moles × 6.02 × 10²³ = approximately 8.4 × 10²⁴ molecules.

That’s roughly 8.4 septillion molecules in a single glass of water. An almost incomprehensibly large number, arrived at through nothing more than logical steps and a few fundamental facts.

The beauty of this approach is that it scales. Want to estimate the molecules in a swimming pool? A raindrop? A cup of tea? The same framework applies. Change the starting volume, follow the steps, and you’ll arrive at a reasonable answer every time.

Why Universities Love This

If you’ve ever wondered why Oxbridge and other top universities include these kinds of questions in their interviews, the answer is simple: they reveal far more than memorised knowledge ever could.

When a student tackles a Fermi problem successfully, they demonstrate several things simultaneously:

They understand fundamental principles. You can’t estimate molecules without genuinely understanding what a mole represents, or why Avogadro’s number matters. Rote memorisation of formulas won’t help here.

They can apply knowledge to unfamiliar situations. This is the exact skill tested in the higher-tier questions on GCSE and A Level papers. It’s also the skill that separates good scientists from great ones.

They stay calm under uncertainty. Science is full of moments where you don’t immediately know the answer. The ability to remain composed, break a problem down, and work systematically towards a solution is invaluable.

They communicate their thinking clearly. In an interview setting, the examiner wants to hear your reasoning out loud. A student who can articulate their thought process: even if they make small errors along the way: demonstrates intellectual maturity and confidence.

These aren’t just “nice to have” skills. They’re precisely what universities are looking for when selecting students for competitive science courses.

Beyond the Calculator: Teaching Real Understanding

One of the things we notice in our tutoring sessions is how many students have become dependent on what we call the “plug and play” method. They identify which formula to use, substitute the numbers, and calculate the answer. It works, up to a point.

But it falls apart the moment they encounter a question that doesn’t fit a familiar template. And those questions are becoming more common, not less, as exam boards increasingly reward genuine understanding over procedural memorisation.

In our sessions, we work to move students beyond this. We want them to see the relationships between mass, volume, and particles so clearly that an estimation question feels like a natural extension of what they already know.

This doesn’t happen overnight. It takes practice, patience, and the right kind of guidance. But when it clicks, the results are remarkable. Students stop fearing the unexpected. They start welcoming it.

We’ve found that one of the most effective ways to build this confidence is through regular exposure to estimation questions in a supportive environment. When students work through these problems with an experienced tutor: someone who can ask the right questions, gently correct misconceptions, and celebrate the “aha” moments: they internalise the approach far more quickly than they would alone.

The Bigger Picture

There’s something genuinely exciting about estimation questions, once you get past the initial intimidation. They remind us that science isn’t really about memorising facts. It’s about using those facts to understand the world.

A glass of water on a kitchen table contains more molecules than there are stars in the observable universe. That’s not just a number: it’s a window into the hidden complexity of everyday life. And a student who can calculate that, using nothing but a pen, some basic knowledge, and clear thinking, has taken a meaningful step towards becoming a real scientist.

Whether your child is preparing for Oxbridge interviews, aiming for top grades at GCSE or A Level, or simply wants to feel more confident in science, learning to tackle estimation questions is time well spent.

Supporting Your Child’s Scientific Thinking

At Success in STEM, we’re running our Easter GCSE Science Revision Course from 7th to 10th April 2026 at Harris Boys Academy in East Dulwich. Our small-group sessions focus on exactly these kinds of skills: building genuine understanding, developing exam technique, and helping students approach unfamiliar questions with confidence rather than panic.

If this feels like the right fit for your child, we’d be very happy to welcome them. You can find more details and book a place at success-in-stem.com/courses.

Because the students who thrive in science aren’t the ones who memorise the most. They’re the ones who learn to think.

Chloe Archard | Oxford-Educated Chemistry Specialist

With over 20 years of teaching experience at some of the UK’s top independent schools, I help ambitious students bridge the gap between hard work and top-tier results. I specialise in GCSE, A Level, and IB Chemistry tuition for students targeting Grade 9s and A*s. Based in the UK but working globally, I provide 1-1 online support for families in South and West London, Dubai, and Hong Kong, ensuring students are perfectly prepared for competitive medical applications and Oxbridge entries. Contact me archardchloe@gmail.com to discuss how I can help your child excel in Chemistry.